An aerial view of the Whittier Narrows Dam in the area between Montebello and Pico Rivera. (Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

Scientists call it California’s “other big one,” and they say it could cause three times as much damage as a major earthquake ripping along the San Andreas Fault.

Although it might sound absurd to those who still recall five years of withering drought and mandatory water restrictions, researchers and engineers warn that California may be due for rain of biblical proportions — or what experts call an ARkStorm.

For the record: 11:45 a.m. Feb. 18, 2019 An earlier version of this story said that when scientists speak of a 900-year storm, it means that such a storm has a 1 in 900 — or .001% — chance of occurring in any given year. The percentage is .1%.

This rare mega-storm — which some say is rendered all the more inevitable due to climate change — would last for weeks and send more than 1.5 million people fleeing as floodwaters inundated cities and formed lakes in the Central Valley and Mojave Desert, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. Officials estimate the structural and economic damage from an ARkStorm (for Atmospheric River 1,000) would amount to more than $725 billion statewide.

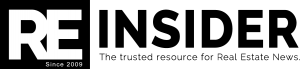

In heavily populated areas of the Los Angeles Basin, epic runoff from the San Gabriel Mountains could rapidly overwhelm a flood control dam on the San Gabriel river and unleash floodwaters from Pico Rivera to Long Beach, says a recent analysis by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

In a series of recent public hearings, corps officials told residents that the 60-year-old Whittier Narrows Dam no longer met the agency’s tolerable-risk guidelines and could fail in the event of a very large, very rare storm, such as the one that devastated California more than 150 years ago.

Specifically, federal engineers found that the Whittier Narrows structure could fail if water were to flow over its crest or if seepage eroded the sandy soil underneath. In addition, unusually heavy rains could trigger a premature opening of the dam’s massive spillway on the San Gabriel River, releasing more than 20 times what the downstream channel could safely contain within its levees.

The corps is seeking up to $600 million in federal funding to upgrade the 3-mile-long dam, and say the project has been classified as the agency’s highest priority nationally, due to the risk of “very significant loss of life and economic impacts.”

The funding will require congressional approval, according to Doug Chitwood, lead engineer on the project.

Standing atop the 56-foot-tall dam recently, Chitwood surveyed the sprawl of working-class homes, schools and commercial centers about 13 miles south of Los Angeles and said, “All you see could be underwater.”

Engineer Douglas Chitwood explains the workings of the Whittier Narrows Dam, which engineers predict would not stand up to a mega-storm. (Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

Engineer Douglas Chitwood explains the workings of the Whittier Narrows Dam, which engineers predict would not stand up to a mega-storm. (Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

The dam — which stretches from Montebello to Pico Rivera and crosses both the San Gabriel and Rio Hondo rivers — is one of a number of flood control facilities overseen by the corps. Throughout much of the year, it contains little water.

A government study, however, used computer models to estimate the effects of 900-year, 7,500-year and 18,000-year storm events.

In each case, catastrophic flooding could extend from Pico Rivera to Long Beach, inundating cities including Artesia, Bell Gardens, Bellflower, Carson, Cerritos, Commerce, Compton, Cypress, Downey, Hawaiian Gardens, La Palma, Lakewood, Long Beach, Lynwood, Montebello, Norwalk, Paramount, Rossmoor, Santa Fe Springs, Seal Beach and Whittier. Officials say as many as 1 million people could be affected.

Among the communities hardest hit in a dam failure would be Pico Rivera, a city of about 63,000 people immediately below the dam. In a worst-case scenario, it could be hit with water 20 feet deep, and evacuation routes would be turned into rivers. Downey could see 15 feet of water; Santa Fe Springs, 10 feet.

In recent years, officials with the U.S. Department of Interior and the U.S. Geological Survey have sought to raise awareness of the threat of mega-storms and promote emergency preparedness. Part of the challenge, however, has been characterizing the scale of such storms. When scientists speak of a 900-year storm, that does not mean the storm will occur every 900 years, or that such a storm cannot happen two years in a row. It means that such a storm has a 1 in 900 — or .1% — chance of occurring in any given year.

The estimates used by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers are intended to protect the region from a storm similar to the one that hit California during the rainy season of 1861-1862. That’s when a series of intense storms hammered the state for 45 days and dropped 36 inches of rain on Los Angeles. So much water fell that it was impossible to cross the Central Valley without a boat, and the state capital was moved temporarily from Sacramento to San Francisco.

“The false sense of security included in the phrase ‘900-year flood’ combined with the promises of 20th century water infrastructure have put us in a bind.”

DAVID REID, WATER HISTORIAN

Some researchers, however, say climate change has cast doubt on 20th-century assumptions. They argue that, in a warming world, regions such as California will experience more whiplashing shifts between extremely dry and extremely wet periods — similar to how California’s long drought was quickly followed by the wettest rainy season on record in 2016-2017. These intense cycles will seriously challenge California’s ability to control flooding as well as store and transport water.

Daniel Swain, a UCLA climate scientist, said hydrological and forecast data used by the corps must be updated.

“The Army Corps’ estimates of the impacts of an extremely serious weather event … are categorically underestimated,” he said. “That’s because we only have about a century of records to refer to in California. So, they are extrapolating in the dark.”

As an example, Swain said until recently it was thought a flood the magnitude of the 1861-1862 event was likely to occur every 1,000 to 10,000 years. New research has changed that view considerably, Swain said.

“A newer study suggests the chances of seeing another flood of that magnitude over the next 40 years are about 50-50,” he said.

Whittier Narrows, Swain added, is therefore just one of “many pieces of water infrastructure that may not be up to the challenge of the brave new climate of the 21st century.”

Men ride horseback in the shadow of Whittier Narrows Dam, which Army Corp of Engineers officials say no longer meets their tolerable-risk guidelines. (Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

Men ride horseback in the shadow of Whittier Narrows Dam, which Army Corp of Engineers officials say no longer meets their tolerable-risk guidelines. (Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

Such was the conclusion of a study conducted by UC Irvine researchers and published recently in the scientific journal Geophysical Research Letters. After examining 13 California reservoirs — most of them over 50 years old — the authors argued that the risk of dam failure was likely to increase in a warming climate. The study cited the 2017 crisis at Oroville Dam, when extreme water flows caused the dam spillway to disintegrate and triggered the evacuation of more than 180,000 people.

In the case of Whittier Narrows Dam, Travis Longcore, a spatial scientist at USC, suggested people had grown complacent about the effectiveness of the area’s flood control system. “People tend to forget about the power of Southern California’s river systems,” he said.

The San Gabriel River ranks among the steepest rivers in the United States, plunging 9,900 feet from boulder-strewn forks in the mountains down to Irwindale. It then meanders in a gravelly channel before arriving at lush Whittier Narrows — a natural gap in the hills that form the southern boundary of the San Gabriel Valley. From there, its flows are tamed in a concrete-covered channel for most of its final journey to the Pacific Ocean.

Now, based on the corps’ findings, L.A. County and municipal officials are working with the federal government to develop emergency plans that can be implemented if necessary before the repair project at the dam is completed in 2026.

Pico Rivera has undertaken an improved preparedness program, but only recently.

Robert Alaniz, a spokesman for Pico Rivera, said the city was using a $300,000 grant from the California Department of Water Resources to revise its existing evacuation plans, which use major thoroughfares crossing the San Gabriel River to the east and Rio Hondo to the west.

Separately, Los Angeles County Supervisor Hilda Solis said she discussed the importance of the Whittier Narrows Dam project with members of Congress during a visit to Washington, D.C., in January.

In the meantime, David Reid, a water historian and expert on the Whittier Narrows area, suggested “the false sense of security included in the phrase ‘900-year flood’ combined with the promises of 20th century water infrastructure have put us in a bind.”

“That’s because a mega-flood is impossible to predict,” he said. “And if the water infrastructure fails, we’re in big trouble.”